My grandfather passed away on a windy April afternoon in 2017. He died at home in Ulladulla, Australia, with my mum and uncle beside him, looking out at the gum trees. Afterward, Mum sat with his body in the cool room before calling the local funeral home to come and pick him up.

Later, the family got together to reminisce about his love for whisky and milk (we called it Poppy Cocktail) and his habit of talking loudly about people we didn’t know while we were all watching television.

My grandfather had what some would call a good death. That isn’t to say the cause of his death was good — the mesothelioma that took his life was swift and brutal — but he had agency to talk about what he wanted, and, importantly, we were lucky enough to have the resources to give it to him.

So, he had the good death — in the home he built, listening to the birds.

The good death

Not everyone is privileged enough to get “a good death.”

End-of-life care can be financially and emotionally taxing, and providing steve madden shoes the elderly the death they desire can be nearly impossible for many families. Seven out of 10 Americans want to die at home, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Only four out of 10 believe they will.

Some believe we need to recalibrate our relationship with death from the ground up.

Sarah Chavez is one of the founders of the Death Positive movement and the executive director of The Order of the Good Death, a community of industry professionals, academics and artists advocating for a healthier relationship with death.

At the core of our relationship with dying and death, Chavez says, is our obsession with youth.

“We’re a youth-centric society. I think a very large part of that is because of our fear of death,” she says.

The US is the largest antiaging market in the world, spending millions of dollars on anti-wrinkle cream, hair dye and cosmetic procedures. We hide our elderly away in nursing homes and hospitals to prolong their lives out of sight — they remind us of our mortality.

“Our elders are just not out and about everywhere,” Chavez says. “You don’t see people age.”

A broken system

According to the National Funeral Directors Association, the median cost of a funeral with viewing and burial is $7,360. For a burial with a cement vault — as required by most cemeteries, notes the NFDA — the cost jumps to around $8,700.

Funeral homes are businesses. This is a multibillion-dollar industry, and while the majority of funeral homes are privately owned, there’s a surprising lack of competition. Service Corporation International is the largest public death care company in the US, with over 1,900 locations in North America and revenue in 2018 of $3.19 billion. The next largest company, StoneMor Partners, made a fraction of that: $316 million. Service Corporation International didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A large part of the business model for these companies involves buying up small funeral homes; trusted family-run ecco shoes businesses used by the community for generations. They keep the name and inject their salespeople and astronomical costs. You want a private viewing to say goodbye? That’ll be $725 dollars for embalming, $250 for cosmetics and $425 for use of the space and staff. That’s over $1,000 before the funeral even starts.

“I just got an email from a woman, an older woman, today, and she said that when she buried her husband, the funeral home told her that it was the law that she had to buy concrete to put over the casket,” Chavez says.

“It’s a lie, and you hear these lies a lot. That’s not a law at all, in any way, shape or form. Concrete blocks [are] not only profitable, but they make it easy to keep everything uniform, so that the lawn maintenance can be done around them.”

So why do cemeteries charge people for things under the guise of “the law”?

Because cemeteries are by and large private properties, so they can essentially make their own rules.

“Of course they’re going to choose what is most profitable for them,” Chavez explains.

Upsells like concrete vaults and embalming are so common they’re seen as requirements, and few are in the position to question it. Many funeral homes require bodies to be embalmed before viewing, and morticians are often taught at mortuary school it’s a necessity.

The truth is, embalming isn’t required at all. No nike sneakers state law requires every body to be embalmed and, most of the time, refrigeration is enough to keep a body in good condition until burial. There’s a common belief that embalming is necessary for sanitizing the body and making it safe to be around. But corpses pose no real threat to public health. The pathogens that decompose bodies aren’t dangerous, nor is the smell of advanced decay.

While corpses aren’t dangerous, there’s mounting proof embalming fluid is. The main chemical in embalming fluid is formaldehyde, which is incredibly toxic. Since the ’80s, studies have shown morticians are at greater risk for several types of cancer because of their exposure to embalming fluid. Once bodies decompose, the embalming fluid seeps into the dirt, potentially contaminating the ground.

But the bigger danger to most Americans isn’t the risk associated with embalming fluid. It’s the risk that a funeral could bankrupt them entirely.

Most Americans aren’t in the financial position to afford a funeral in the first place.

A study by the Federal Reserve in 2018 found only 61% of American adults could afford an unexpected expense of $400, while a whopping 39% would not be able to afford it without having to sell possessions or go without food or other necessities. For most people, an unexpected $8,000 funeral bill would be emotionally and financially devastating.

“To bury someone is expensive. None of it has anything to do with a real connection to religion or ethnicity — it all has a connection to dollars,” Jeff Jorgenson says.

Jorgenson runs Elemental Cremation and Burial, a green funeral home in Seattle, and co-owns Clarity Funerals and Cremation.

Traditions and religious practices are strong and will never really go away. But in some cases, cost wins out over tradition. Even deeply religious families who would usually abhor cremating their dead are opting for cremation in many cases, Jorgenson notes. “It makes no sense to spend $14,000 to bury grandma when they can’t pay for food.”

Too often, bereaved families scramble to cover costs for a memorial after a loved one unexpectedly passes away. Many families turn to online funding — GoFundMe proudly describes itself as the leading online funeral fundraiser, with 125,000-plus campaigns raising $400 million a year. Other families aren’t so lucky.

“Where I’m from, here in California, what we see a lot are just people standing on the side of a road with a cardboard sign asking for money for a funeral,” Chavez says. “Especially in poor rural communities, this is the norm. You see a lot of funeral car washes where families will stand outside gas stations, and what they’re doing is they’re raising money to pay for the funeral.

“Families don’t know that they often have a choice — no one should have to pay that much.”

100 years of tradition

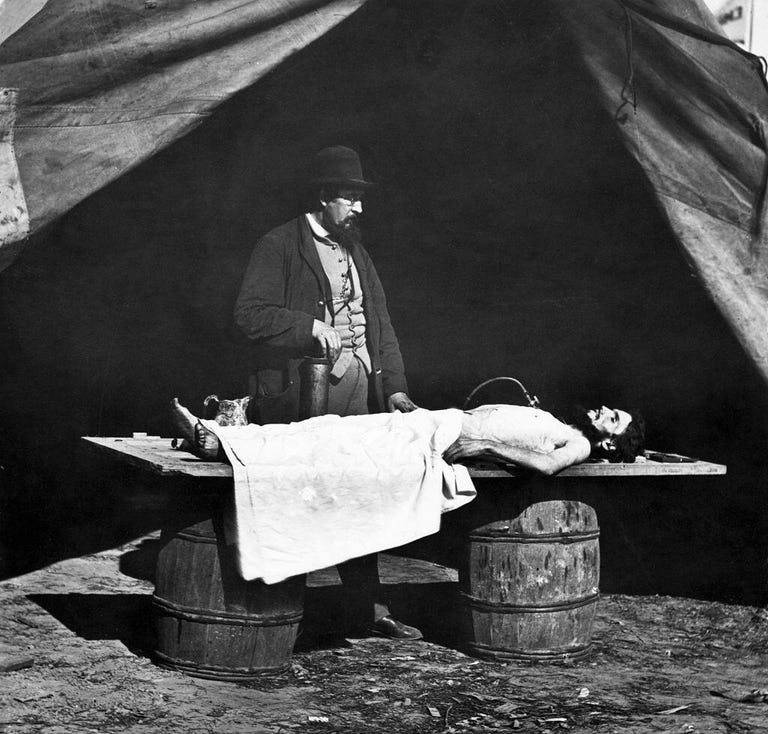

Before 1861, burying the dead was a family affair. When someone died — usually at home — it was their family that washed and prepared them. The body would be laid out in the nicest room in the house and people would come and pay their respects.

That simple practice existed for generations, until the Civil War and the beginnings of the modern American funeral industry. The almighty dollar has dictated our burial customs ever since.

On May 24, 1861, Col. Elmer Ellsworth became the first Union soldier killed in the Civil War. Due to the heat and distance, soldiers’ remains often went through advanced stages of decomposition by the time they reached home. After hearing of his death, Dr. Thomas Holmes — the father of modern embalming — offered his services to the Ellsworth family. They accepted and Colonel Ellsworth became the first Civil War soldier to be embalmed.

Before long, it wasn’t uncommon to see amateur undertakers set up shop on the outskirts of battlefields, ready to make good money embalming the dead. Competition was fierce, and the burgeoning industry was wholly unregulated.

The years after World War II were another turning point for the Great American Funeral. The economic boom of the 1950s meant people had more money than ever to flaunt. That didn’t stop with the shiny Cadillac or television set: An extravagant funeral was just another way to show your wealth.

Funeral trends were dictated heavily by Forest Lawn cemetery and its general manager, Hubert Eaton.

Eaton was “the original upbeat undertaker,” writes Caitlin Doughty, co-owner of Clarity Funerals and Cremation with Jorgensen, in her asics shoes memoir Smoke Gets in Your Eyes. He took the dull, sad funerals of yore and injected them with euphemisms (a person didn’t die, they took their leave), embalming fluid and bright pink satin-lined caskets.

In short, death in America has become a commodity. Our customs and traditions are dictated by industry, rather than spirituality or values. Our fear of getting old and dying prevents us from talking about it, so we perpetuate the same customs — customs designed specifically for profit.

Say you don’t want to spend eternity in a cemetery, in a mahogany coffin, with wire holding your mouth closed. What do you do?

“My new thing is promoting micro-conversations,” Jorgenson told me. “Instead of this ‘I want to sit down and talk about my final arrangements’ and all of a sudden it’s this huge conversation. It’s more saying ‘you know what — I think I want to be cremated,’ and that’s it.”

Jorgenson, along with Doughty, is one of the founding members of The Order of the Good Death. The group promotes books, holds events and cultivates online communities designed to open up a dialogue about death and our relationship with it.

+ There are no comments

Add yours